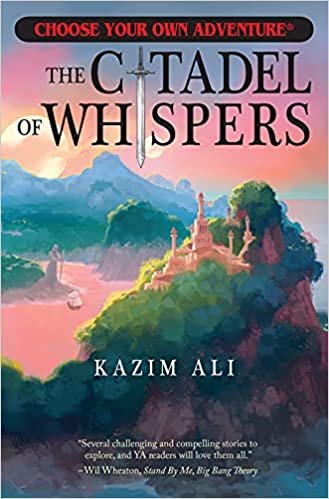

By Kazim Ali

Making Krishi, the main character of my new Choose-Your-Own-Adventure book, The Citadel of Whispers, a gender-neutral character was never supposed to be a big deal. In the classic line of books, the protagonist characters—the character the reader assumed the persona of—was always written as gender neutral. It was the marketing and art departments of the original publisher that had to make decisions about what the cover would look like and what the internal art would look like. It was felt at the time that though girls might read a book with a boy protagonist the reverse might not be true. While most of those early books depicted a boy in the cover art and internal art, the text itself never really gendered the character by either behavior, appearance, or in the action of the text.

It was a short leap from that concept to the notion that characters themselves in the book might have various relationships to gender. Not only did I carefully construct the main character, Krishi, as someone who could either be identified as a boy, a girl, or gender neutral, but other characters in the book also have different relationships to classic gender stereotypes and to fantasy stereotypes as well. For example, Krishi’s two main friends have abilities different that one might expect. Zara, a girl, is the best fighter in the school but is also upset at having to cut her long hair to conform to the gender-neutral appearance that all Whisperers are expected to have in order to be better spies. Saeed, a small boy, is often thought of as physically weak but at several points in the story he manages to defeat fighters bigger and stronger than him by his cunning.

Tough independent girls appeared many times before in children’s literature of course, but it was probably Sally Kimball, created by Donald J. Sobol as part of his Encyclopedia Brown series, who was the first real bruiser. She was 10 years but often bested larger boys, often giving 14-year-old Bugs Meany an actual black eye to match the metaphorical black eye he got when Encyclopedia exposed his role in various petty crimes. Sally wasn’t a well-rounded hero. She was the muscle to Encyclopedia’s fey, retiring brains. It’s interesting to note that the not-quite-feminist icon Buffy Summers of Buffy the Vampire Slayer was also not overly noted for their intelligence. The first round of girl action heroes could be as buff and butch as the boys but she couldn’t have it all.

The Whisperers in The Citadel of Whispers, know that in their work they have to be able to pass as anything. The book actually opens with a martial arts class in which the students—boys and girls and everyone else—have to engage in combat while corseted into restrictive dresses. Their normal clothes are gender neutral tunics and pants, and their hair must be uniformly shoulder length, neither longer nor shorter. Other characters in the book also defy gender expectations. The combat teacher is an athletic woman, while the dance instructor is a slim man; the rogue-like pirate ship captain (think the Han Solo-type) is a sixty-something year old woman with a penchant for taking swigs out of a flask and smoking tobacco from a long pipe.

Since fantasy is a genre with such historic tropes (around both race and gender), I knew I couldn’t write a story with the same figures. Princess Leia of Star Wars is a warrior woman for sure (I once heard that if you calculate the ratio of shots fired to successful hits, Leia is the best shot of all the characters in the series), but her primary attribute in the original trilogy still leaned into the traditional role of damsel in distress in need of rescue. It wasn’t until the sequel trilogy that the world around her had evolved enough for her to be fully depicted at what was only winked at in a few scenes of the original: she was the political and military leader of the resistance.

I also wanted to work against the norm of most fantasy milieux: a pseudo medieval European context in terms of the castles, the costumes, the social roles. Rather than Tolkien or Lewis (or Brooks or Eddings, who drew from those two), I drew instead upon the wonderful Amar Chitra Katha comics of my childhood, describing Indian architecture and giving most—but not all—the characters Indian names. Innovation is also a firm tradition in speculative fiction. When Anne McCaffrey created her world of the dragonriders of Pern with the first novel in 1968, she created a matriarchal political structure in which homosexuality was an ordinary part of life. The characters who disapproved of it were seen is reactionary and out of touch and were almost always villainous in the context of the story.

Like Krishi, most characters in The Citadel of Whispers, have their own relationship to gender, some more traditional—like Sandhya, the martial arts instructor, or Etheldreda, a gardener with big plans—and others, like the master Whisperer Shivani or the sullen new student Arjun, each disrupt expectations a reader might have. There are trans characters, revealed as such in the text, and others might be read that way. There is at least one character who is written as a drag performer, but is not revealed that way in the text. Hey, I have to save something for Book 2!

In the end, the point was not to be “political” about gender but to be inclusive. The point was to write a book that any boy or girl could read and not feel excluded from, more importantly any young person who had a complicated relationship to their own gender, or wasn’t sure what it meant to them, could read this book as well and feel that they had a home in it. An imagined world ought to include everyone with an imagination.

KAZIM ALI is an award-winning LGBTQ+ author and the Chair of the Department of Literature at the University of California, San Diego. His new book The Citadel of Whispers,, is available now. Learn more on his website kazimali.com