by Nancy King

I’ve always been a storyteller yet there were stories I could not tell, others I tried to tell, but no one wanted to hear them. Editors rejected the memoir I wrote as part of my PhD thesis as “too bleak and troublingly personal.” Agents rejected Morning Light, a novel that was a fictional account of my life, as being too dark. I felt ashamed of who I was and what I’d experienced. To keep going, I created a cheerful, strong persona that helped to disconnect me from the darkness I lived with. I felt emotionally isolated, filled with shame that my life was too grim to talk about.

After returning from a vision quest in 2016, I started writing what I thought would be my sixth novel, only what came out was nonfiction—stories of my life. No matter how I tried, I couldn’t create a character whose life was not mine. It was a struggle similar to the one years ago when every popping out story I wrote was about sexual abuse and violence despite concerted effort to write differently.

So, I gave up and gave in, grudgingly allowing what wanted to come out to emerge. To distance myself from the emotional content I tried writing third person, past tense, naming no names, but this became impossible. There are only so many words for she, woman, her... Even worse, the writing was impassive, with no emotional content, more like journalism, which was how one of my therapists described the way I talked about my life.

I felt desperate—wanting to write—but not wanting to write what I was writing. I know the feeling when something inside me wants to come out yet I didn’t want to write about my life. I wanted to write fiction, about someone who was not me, leading a life that was not mine, with problems I had never experienced. Yet something inside was pushing me to tell the truth just as strongly as something inside was pulling me back into inner darkness. To stop the struggle, which was uncomfortably intense, I gave in. There was nothing left to do but write first person, present tense. This opened a floodgate of memories, painful, dark, emotionally upsetting. I wrote associatively, not caring about chronology, not caring about age or place. It was hard going because writing first person, present tense brought me back to the time and place of the actual experience. I could smell and taste and feel my four-year-old terror when I wrote about what happened with my uncle—experiences I could never talk about, never even let myself acknowledge, until the vision quest when I was 80 years old.

I kept writing, but I worried. Was it too much me me me? Would what I’d written interest anyone else? I sent a few chapters to a former student, asking her if any of it mattered. She wrote back that she was going through a difficult time emotionally, that my writing was helping her feel she wasn’t alone, would I please keep writing and sending her what I’d written. That was enough to keep me going.

When I’d written about 300 pages, I sent the material to my editor. “Nancy,” she said, “the writing is fine, but it has to be chronological. I need to read how your voice changes as you grow, how you develop as a woman. Right now, I can’t tell how old you are, where you are, with whom you’re living. It’s all a jumble and vitiates the power of your writing.”

Oy! I’m not good with computer stuff. The prospect of rearranging so many chapters was daunting. I printed out the book, manually re-organized the chapters so they were chronological, then, with the real pages in hand, I slowly rearranged what I’d written to make the chapters chronological. This allowed me to see what was missing, what needed to be tossed. I also realized the arc of the book was about healing from childhood trauma and subsequent abuse as an adult. The bad choices I’d made as an adult, that I knew at the time were bad choices, but was unable to not make them, which had always puzzled me, now made sense. At the time, I didn’t know that what I couldn’t acknowledge was shaping the choices I made. After writing the memoir I was able to fit together pieces of the puzzle of my life that had never fit before.

Perhaps I was now able to consciously write stories about my life because of what happened toward the end of the vision quest. As part of the process, each of the participants talked about their experience in the woods. Most people focused on the difficulty of being without family, phone, books, social media, or being in a wilderness without a tent. Not wanting to talk, I waited until everyone else had spoken. When everyone’s eyes were focused on me there was no way to remain silent. The compassionate attention of the group allowed me to speak about a traumatic relationship and abortion, sparing no details, the shame I felt at not being able to say no to my parents or the man. I expected blame. What I got was lovingkindness, acceptance, caring, deep listening—something I’d never experienced before, except perhaps in a therapist’s office, but even there I was never able to speak without censoring myself.

Looking back, I now understand that telling the story I told at the vision quest shifted my sense of myself. The change enabled me to be truthful when talking about my life. I found people who wanted to hear, were able to listen and respond with caring. They didn’t turn away or judge or condemn me. This broke the grip of the relentless shame and blame with which I’d lived, allowing me to break my lifelong pattern of silence.

Writing Breaking the Silence, finding the wherewithal to tell the stories of my life without censoring, enabled me to break through my families’ silence, lies, denial, blame, and shame.

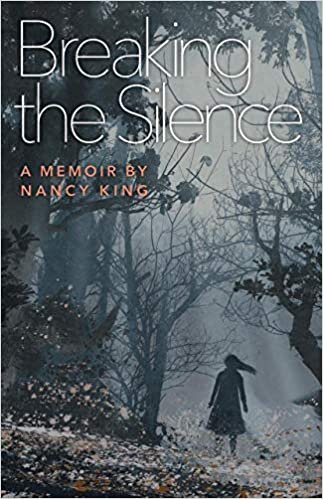

A friend, who read and liked the manuscript sent it to a local press, Terra Nova Books. They offered to publish it, which surprised and pleased me. They suggested titles. I didn’t like them. I suggested titles. None of us liked them. Nothing anyone came up with seemed right. Then, the friend who sent the manuscript to Terra Nova Books suggested the title, Breaking the Silence, which immediately felt right and descriptive.

The publication of Breaking the Silence has made it possible for me to begin healing from the trauma and abuse, shame and blame with which I’ve lived all my life. Telling the story of our lives is the first step toward becoming authentically who we are.

What is your story?

Nancy King, Ph.D., is a writer and playwright whose nonfiction, plays, and novels have won numerous awards. Her novel, The Stones Speak, has been optioned for a movie. She facilitates workshops in creative expression, playmaking, and world literature in the U.S. and abroad. Living in Santa Fe, N.M., she finds inspiration in storytelling, weaving, writing, and hiking in the mountains.