By: J. A. Tyler

I love telling students of writing that whatever they put on the page becomes truth in the context of that world. This is to me, and I hope to them, mind-altering. Once you write it, it is fact, no matter what genre or style you prefer. What a glorious, unbelievable, crazy feat that really only exists in the realm of writing. Write the words, and it is so.

For magical realism, a genre I work in almost exclusively, that joy becomes doubled, because what we’re making into “fact” in a work of magical realism is wholly unexpected and often counter to what we understand or know about our world, and yet, it becomes truth. In Only and Ever This, where a mother is attempting to mummify her twin sons in order to stop them from growing up, a kind of Peter Pan syndrome but from the parental perspective, I didn’t have to spend any time processing whether this type of mummification was possible. Some research on mummies is loaded into the structure of the novel, but I didn’t need anything else. Once I wrote that she was practicing mummification on a cat, it became so. And when that cat is reawakened, its heart wrapped in mud and rainwater, readers have to accept it. So the mother can mummify just a portion of one son’s arm, testing the waters of her abilities, while allowing me to focus on the emotional and moral struggle of the task rather than with any challenges presented by physiology or biology.

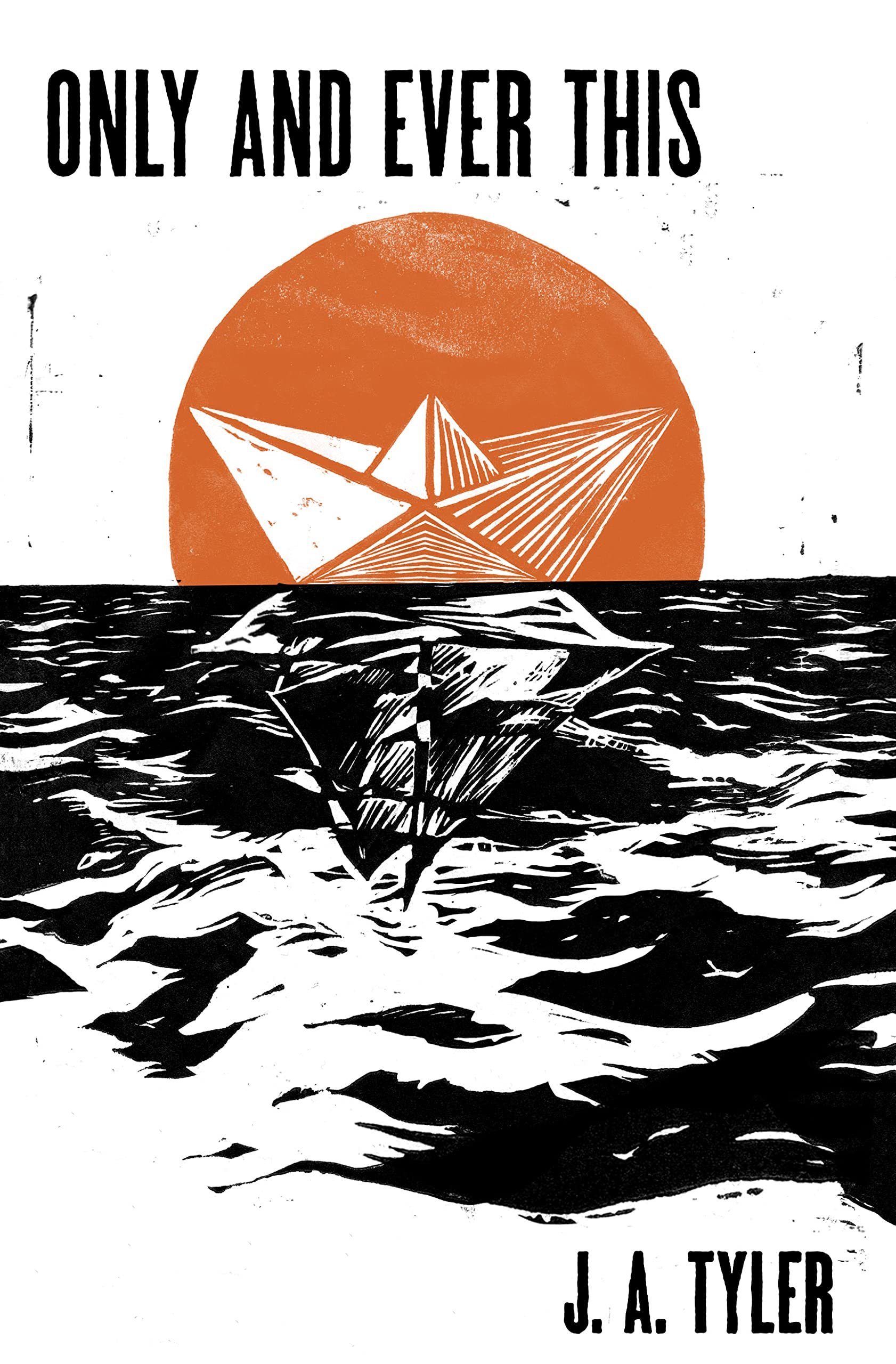

Also in the book, the boys’ father is a pirate, and because it is a work of magical realism, I don’t need to worry about what it means to be a pirate in a modern era, or even in the sort of stylistically 1980s vibe of my novel. He is a pirate and he sails off to sea seeking immortality, either in the form of treasure or, more significantly, in the form of a vampire. Do vampires exist? They might, because the father is searching for them, and he believes it, so we as readers have to believe in it too, at least in his world. Magical realism takes the burden away from fact and places it squarely on imagination.

The boys too, these twin sons, they fall in love with the ghost of a girl up the street. She is ethereal, rife with lightness and beauty, and they want to build a relationship with her before she disappears, before she becomes entirely see-through. In the novel, that becomes fact, just as the arcade they hang out in, the marbles they shoot, and the bikes they ride are fact. With magical realism, a muddy undead bully of a kid can haunt the town, a cat can be dissected and resurrected, and ghosts and mummies and pirates can co-exist in a township where the rain never ends. When we write it, it is so.

For writers (and readers) of magical realism, we don’t have to take the characters to another planet, to some faraway, fictional world. We can center them in our world, with its battered relationships and gray skies, with its sunlight struggling through clouds and waves bleating on the shore. We can take what we know and blend it with what we don’t. Magical realism allows us the horrific and beautiful ability to house any monster, literal and figurative, inside our own tragic world.

J. A. Tyler is the author of Only and Ever This and The Zoo, a Going (both from Dzanc Books). His fiction has appeared in Denver Quarterly, Hayden’s Ferry Review, Diagram, Black Warrior Review, Fairy Tale Review, and The Brooklyn Rail among others. He lives in Colorado. For more: www.jasonalantyler.com, twitter, instagram